How has my work contributed to the development of theory?

In addition to teaching measurement science and applied statistics, and engaging in selected consulting projects about consumers of good and services, I am also an academic researcher who has been very active in the area of media effects and international communication.

As I look back on the 30+ years that I have been an academic researcher, here are three highlights of my contributions to theory over the years: The Susceptibility to Imported Media (SIM) model, the Model of International Public Opinion (MIPO), and the Integrated Process Model of Media Effects (IPMME).

Contribution 1 - The model of Susceptibility to Imported Media (SIM)

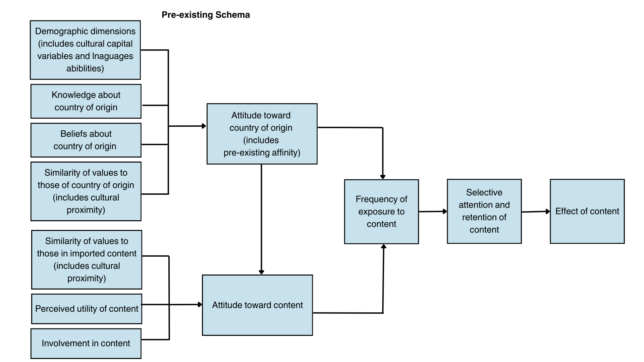

Description: For many decades, the dominant paradigm for explaining and labeling the impact of exposure to imported media had been what is called “Cultural Imperialism”. After looking into the claims made by its proponents, I found that empirical evidence was not consistent with the perspectives put forth by those who advocate Cultural Imperialism. In 2002, I edited a book titled “The Impact of International Television: A Paradigm Shift”. In this book, I proposed that the impact of international TV is not homogeneous and that some people are more susceptible to being exposed to and influenced by imported media than others. I also gave a new label for an instance when impact is detected: Media-Accelerated Cultural Diffusion. I proposed the model below based on a thorough review of the literature and the results of my meta-analysis co-authored with the late John Hunter

For a full description of the SIM model, please see:

Elasmar, M. G. (2002). An alternative paradigm for conceptualizing and labeling the process of influence of imported television programs. In M. Elasmar (Ed.), The impact of international television: A paradigm shift (pp. 157-169). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

A sample of articles that have cited the SIM model shows that the researchers span the globe:

Bowman, N. D., Jöckel, S., & Dogruel, L. (2012). A question of morality? The influence of moral salience and nationality on media preferences. Communications-The European Journal of Communication Research, 37(4), 345-369.

Chung, Y. K., Yu, S. K., Lee, H. E., & Kim, J. H. (2016). Female Viewers’ Korean Drama Consumption in the US. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 16(9), 40-50.

김병현, & 장병희. (2016). The Influence of the Existing Knowledge and Attitude toward Countries of Origin on Consumption of Imported Chines TV Drama – Focusing on Members of a Korean Online Fan Community for Chinese TV Series. 사회과학연구, 23(4), 27-52.

Fung, T. K., Yan, W., & Akin, H. (2018). In the eye of the beholder: How news media exposure and audience schema affect the image of the United States among the Chinese public. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(3), 443-472.

Möhring, W., & Schlütz, D. (2013). Standardisierte Befragung: Grundprinzipien, Einsatz und Anwendung. Handbuch standardisierte Erhebungsverfahren in der Kommunikationswissenschaft, 183-200.

Schlütz, D. (2012). Der Prozess grenzüberschreitender Medienwirkungen. Das Susceptibility to Imported Media (SIM)-Modell am Beispiel US-amerikanischer Fernsehserien. Medien und Kommunikationswissenschaft, 1, 183.

Schlütz, D., Emde-Lachmund, K., Schneider, B., & Glanzner, B. (2017). Transnational media representations and cultural convergence–An empirical study of cultural deterritorialization. Communications, 42(1), 47-66.

Schlütz, D., & Schneider, B. (2014). Does cultural capital compensate for cultural discount? Why German students prefer US-American TV series. Critical reflections on audience and narrativity: New connections, new perspectives, 7-26.

Schlütz, D., & Schneider, B. (2014). CHAPTER EIGHT ‘AMERICA’S FAVOURITE SERIAL KILLER’: ENJOYMENT OF THE TV SERIAL DEXTER. Contemporary television series: Narrative structures and audience perception, 115.

Schlütz, D., & Schlütz, D. (2016). V Hochwertige Unterhaltungsrezeption: Die Modellierung des Unterhaltungserlebens von Quality TV. Quality-TV als Unterhaltungsphänomen: Entwicklung, Charakteristika, Nutzung und Rezeption von Fernsehserien wie The Sopranos, The Wire oder Breaking Bad, 173-255.

Wessler, H., Brüggemann, M., Wessler, H., & Brüggemann, M. (2012). Folgen grenzüberschreitenden Kulturkontakts bei den Mediennutzern. Transnationale Kommunikation: Eine Einführung, 159-178.

What does the SIM model say?

The SIM model predicts that the segment of viewers most likely to be susceptible for being positively influenced by imported TV programs is that which closely fits these characteristics:

- Have a pre-existing positive attitude toward that country is perceived to be the source of the imported TV program. This is consistent with the findings concerning pre-existing affinity reported by Elasmar and Sim (1997): having friends and/or relatives in the U.S. and having learned favorable information from one’s parents about the US are positive predictors of exposure to U.S TV programs and positive indirect predictors of liking U.S. fast food. This profile characteristic is also compatible with the findings on persuasion by Chaiken and Eagly (1983), the results concerning intergroup relations reported by Bornstein (1993) and the consumer behavior findings related to “country of origin” research reported by Verlegh and Steenkamp (1999);

- Are compatible linguistically with the imported TV program. Straubhaar (2003) found that linguistic compatibility was a clear predictor of exposure to international TV;

- Have values that are compatible with the source and contents of the imported TV program. Straubhaar (2003) found that cultural proximity and cultural capital predict a viewer’s exposure to international TV programs and facilitate his/her/their decoding of the message imbedded in that program. This requirement of a compatible value schema is also consistent with the findings about interpreting Dallas reported by Liebes and Katz (1993), and processing of new educational information reported by Renzulli and Dai (2001);

- Are not negatively prejudiced against the source or content. This is consistent with the literature about the contact hypothesis summarized by Stephan (1987);

- Perceive one or more “utilities” for self in the content of the imported TV program and are involved in such content. The concept of utility was put forth by Katz (1968) combined with the concept of involvement that is central to the persuasion literature (see Cacioppo, Petty, Kao, & Rodriguez, 1986; Johnson & Eagly, 1989; Stiff, 1986).

- Will frequently watch one or more imported TV programs stemming from the same foreign source. In this case, an interaction between frequency of exposure to imported programs and pre-existing affinity toward the source of those programs will produce the strongest effects.

Contribution 2 - A Preliminary Model of International Public Opinion (MIPO): In Country B about a Prominent Foreign Policy Adopted by Country A

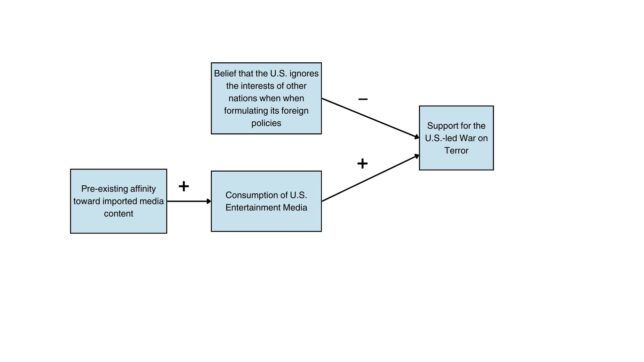

Description: After the 9/11, 2001 terrorist attack on the United States and the subsequent launching of the U.S.-led war on terror, there was keen interest by researchers in understanding whether the public overseas will support this war. As an extension of the SIM model, and relying on the results of more recent studies, I proposed a Model of International Public Opinion (MIPO) and reanalyzed multinational data collected by The Pew Center’s Global Attitudes Project to test this model in 7 different countries.

For a full explanation of how the model was built and tested, please see:

Elasmar, M. G. (2007). Through their eyes: factors affecting Muslim support of the U.S.-led War on Terror. Marquette Books.

“From the literature reviews on public opinion and foreign policy, exposure to international news, and exposure to imported entertainment TV programs, we can identify numerous potential predictors and/or schema components of international public opinion. Altogether, they can be categorized into the following general building blocks of a theoretical model of public opinion formation and variation: Demographics, Predispositions, Media Exposure, Beliefs, and Attitudes. The demographic predictors can be conceptualized as potential antecedents of individuals’ schemas. The other predictors (i.e., predispositions, media exposure, beliefs and attitudes) can be conceptualized as potential schema components.

In addition to the above, since the dependent variable that is the focus of this book is “international opinion about a prominent foreign policy adopted by a country other than one’s own,” this dependent variable subsumes the notion of “a foreign country” (e.g., the United States for those living elsewhere) and “the topical focus of the foreign policy” (e.g., terrorism). It is thus reasonable to take into account not only beliefs and attitudes about the “foreign country,” but also beliefs and attitudes pertaining to the “topical focus of the foreign policy.” The building blocks included in Table 2.5, in addition to beliefs and attitudes about the “topical focus of the foreign policy,” can be proposed as components of a theoretical model that can potentially explain the variation in the public opinion of people in country B toward the foreign policies of the government in country A (see Figure 2.5).” (p. 75).

After testing a separate model for each of the 7 countries, I arrived at a final model that is shared across all 7 countries. In a way, this final model shows the components of the shared thought process regarding the war on terror and their interrelationships.

A final MIPO from Elasmar (2007):

The Relationships in the Model of International Public Opinion (MIPO) Tested for Muslims in Seven Countries

Direct Effects

Muslims’ support for the U.S.-led war on terror is directly predicted by their belief that the United States ignores their countries’ interests when making foreign policy decisions and their consumption of U.S. entertainment media. These relationships suggest that the less they believe that the United States ignores their countries’ interests, and the more probable they are to consume U.S. entertainment media, the greater is the probability that they support the U.S.-led war on terror.

Mediating variables

Consumption of U.S. Entertainment Media: In addition to being a direct and positive predictor of support for the U.S.-led war on terror, consumption of U.S. entertainment media is, itself, influenced by another variable: preexisting affinity toward imported media. The more receptive they are to imported media, the more probable they are to consume U.S. entertainment media” (from Elasmar, 2007).

Contribution 3 - An Integrated Process Model of Media Effects (IPMEE)

Description:

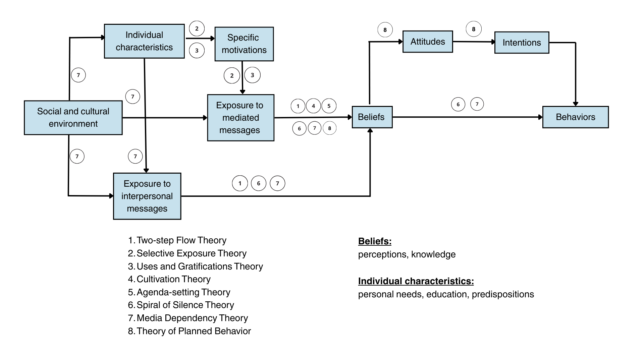

Academic researchers are often criticized for developing multiple theories that seem to be independent of one another, even though they are all designed to explain a part of the same process. In 2018, I decided to review what I considered to be classical theories of media effects to integrate the knowledge that they put forth. This effort resulted in the model below:

For a full account of how this integration took place, please see:

Elasmar, M. G. (2018). Media Effects. In Napoli. P. M. (Ed.), Mediated communication (Vol. 7) (pp. 29-53). De Gruyter, Inc.

From Elasmar (2018):

“The first step towards an integrated theory across media effect and related theories is to identify the outcome variables. In this case, key outcome variables across all seven media effect theories fall under media exposure, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (see Elasmar 2008, chapter 2, for definitions of beliefs and attitudes). Once the outcome variables are identified, instead of reinventing the wheel, the next step is to determine whether there is an existing theoretical framework that deals with these outcome variables and that can be built upon.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen 1985), in part, focuses on the interrelationships between beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Although not a traditional communication theory, it nevertheless provides us with a solid base to begin the integration of media effect theories. As a starting point, we can certainly adopt the structure of interrelationships that it specifies among three key outcome variables. TPB has been tested in thousands of investigations and the structure that it specifies among beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors has been found to be very stable over time. With respect to these three variables, TPB generally specifies that beliefs about topic A drive attitude about topic A, which in turn drives behavioral intentions related to topic A and, in turn, drive the actual behaviors related to topic A.

The first component of an integrated media effects theory is a four-variable sequence beginning with beliefs and ending with behaviors. Media exposure is a core variable of all media effect theories. It is an outcome variable for Uses and Gratifications and Selective Exposure and the main predictor for all others. Exposure to mediated messages can then be added as an immediate antecedent of the “beliefs” component of the model. The Two-Step Flow Theory contends that the influence of media exposure might be mitigated by interpersonal influence. As a result, interpersonal messages can be added as a competing predictor onto beliefs. Selective Exposure and Uses and Gratifications propose that media exposure will be a function of specific motivations and individual differences. As a result, these two components can be added to the model as antecedents of media exposure.

Media Dependency Theory tells us that none of these relationships can occur in a vacuum as they are a function of the social and cultural environment in which the audience members/ media users exist. We can thus add social and cultural environment variables as antecedents of the entire process. A starting point Integrated Process Model of Media Effects emerges and is presented in Figure 1. It is important to note that each building block in the model consists of a variable category and each category can accommodate dozens of specific variables. The objective of proposing this starting point process model is that it is hoped that it would encourage the new generation of media effects scholar to take a more comprehensive approach to the study of media influence and, as such, overcome the limitations that characterize the approach taken by earlier scholars.” (from Elasmar, 2018).